https://algorithmsoup.wordpress.com/2019/01/15/breaking-an-unbreakable-code-part-1-the-hack/

RSA encryption allows for anyone to send me messages that only I can decode. To set this up, I select two large random primes and

and  (each of which is hundreds of bits long), and release their product

(each of which is hundreds of bits long), and release their product  online for everyone to see;

online for everyone to see;  is known as my public key. In addition, I pick some number

is known as my public key. In addition, I pick some number  which shares no factors with

which shares no factors with  or

or  and release it online as well.

and release it online as well.

The beauty of RSA encryption is that using only the information I publicly released, anyone can encode a message they want to send me. But without knowing the values of and

and  , nobody but me can decode the message. And even though everyone knows my public key

, nobody but me can decode the message. And even though everyone knows my public key  , that doesn’t give them any efficient way to find values for

, that doesn’t give them any efficient way to find values for  or

or  . In fact, even factoring a 232-digit number took a group of researchers more than 1,500 years of computing time (distributed among hundreds of computers).

. In fact, even factoring a 232-digit number took a group of researchers more than 1,500 years of computing time (distributed among hundreds of computers).

On the surface, RSA encryption seems uncrackable. And it might be too, except for one small problem. Almost everyone uses the same random-prime-number generators.

A few years ago, this gave researchers an idea. Suppose Bob and Alice both post public keys online. But since they both used the same program to generate random prime numbers, there’s a higher-than-random chance that their public keys share a prime factor. Factoring Bob’s or Alice’s public keys individually would be nearly impossible. But finding any common factors between them is much easier. In fact, the time needed to compute the largest common divisor between two numbers is close to proportional to the number of digits in the two numbers. Once I identify the common prime factor between Bob’s and Alice’s keys, I can factor it out to obtain the prime factorization of both keys. In turn, I can decode any messages sent to either Bob or Alice.

Armed with this idea, the researchers scanned the web and collected 6.2 million actual public keys. They then computed the largest common divisor between pairs of keys, cracking a key whenever it shared a prime factor with any other key. All in all, they were able to break 12,934 keys. In other words, if used carelessly, RSA encryption provides less than security.

security.

At first glance this seems like the whole story. Reading through their paper more closely, however, reveals something strange. According to the authors, they were able to run the entire computation in a matter of hours on a single core. But a back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that it should take years to compute GCD’s between 36 trillion pairs of keys, not hours.

So how did they do it? The authors hint in a footnote that at the heart of their computation is an asymptotically fast algorithm, allowing them to bring the running time of the computation down to nearly linear; but the actual description of the algorithm is kept a secret from the reader, perhaps to guard against malicious use. Within just months of the paper’s publication, though, follow-up papers had already discussed various approaches in detail, both presenting fast algorithms (see this paper and this paper), and even showing how to use GPUs to make the brute-force approach viable (see this paper).

There’s probably a lesson here about not bragging about things if you want them to stay secret. But for this post I’m not interested in lessons. I’m interested in algorithms. And this one turns out to be both relatively simple and quite fun.

Algorithm Prerequisites: Our algorithm will deal with integers having an asymptotically large number of digits. Consequently, we cannot treat addition and multiplication as constant-time operations.

For -bit integers, addition takes

-bit integers, addition takes  time. Using long multiplication, multiplication would seem to take

time. Using long multiplication, multiplication would seem to take  time. However, it turns out there is an algorithm which runs in time

time. However, it turns out there is an algorithm which runs in time  .

.

Computing the GCD naively using the Euclidean algorithm would take time. Once again, however, researchers have found a better algorithm, running in time

time. Once again, however, researchers have found a better algorithm, running in time  .

.

Fortunately, all of these algorithms are already implemented for us in GMP, the C++ big-integer library. For the rest of the post we will use Big-O-Tilde notation, a variant of Big-O notation that ignores logarithmic factors. For example, while GCD-computation takes time , in Big-O-Tilde notation we write that it takes time

, in Big-O-Tilde notation we write that it takes time  .

.

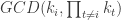

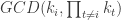

Transforming the Problem: Denote the set of public RSA keys by , where each key is the product of two large prime numbers (i.e., hundred digits). Note that

, where each key is the product of two large prime numbers (i.e., hundred digits). Note that  is the total number of keys. Rather than computing the GCD of each pair of keys, we can instead compute for each key

is the total number of keys. Rather than computing the GCD of each pair of keys, we can instead compute for each key  the GCD of it and the product of all the other keys

the GCD of it and the product of all the other keys  . If a key

. If a key  shares exactly one prime factor with other keys, then this provides that prime factor. If both prime factors of

shares exactly one prime factor with other keys, then this provides that prime factor. If both prime factors of  are shared with other keys, however, then the computation will fail to

actually extract the individual prime factors. This case is probably

rare enough that it’s not worth worrying about.

are shared with other keys, however, then the computation will fail to

actually extract the individual prime factors. This case is probably

rare enough that it’s not worth worrying about.

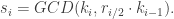

The Algorithm: The algorithm has a slightly unusual recursive structure in that the recursion occurs in the middle of the algorithm rather than at the end.

At the beginning of the algorithm, all we have is the keys,

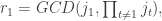

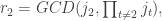

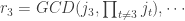

The first step of the algorithm is to pair off the keys and compute their products,

Next we recurse on the sequence of numbers , in order to compute

, in order to compute

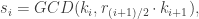

Our goal is to compute for each key

for each key  . The key insight is that when

. The key insight is that when  is odd,

is odd,  can be expressed as

can be expressed as

and that when is even,

is even,  can be expressed as

can be expressed as

To see why this is the case, one can verify that the term on the right side of the GCD is guaranteed to be a multiple of , while also being a divisor of

, while also being a divisor of  . This, in turn, implies that the GCD-computation will evaluate to exactly

. This, in turn, implies that the GCD-computation will evaluate to exactly  , as desired.

, as desired.

Computing each of the ‘s in terms of the

‘s in terms of the  ‘s and

‘s and  ‘s completes the algorithm.

‘s completes the algorithm.

Bounding the Running Time: Let denote the total number of bits needed to write down

denote the total number of bits needed to write down  .

Each time the algorithm recurses, the total number of bits in the input

being recursed on is guaranteed to be no more than at the previous

level of recursion; this is because the new inputs are products of pairs

of elements from the old input.

.

Each time the algorithm recurses, the total number of bits in the input

being recursed on is guaranteed to be no more than at the previous

level of recursion; this is because the new inputs are products of pairs

of elements from the old input.

Therefore each of the levels of recursion act on an input of total size

levels of recursion act on an input of total size  bits. Moreover, the arithmetic operations within each level of recursion take total time at most

bits. Moreover, the arithmetic operations within each level of recursion take total time at most  . Thus the total running time of the algorithm is also

. Thus the total running time of the algorithm is also  (since the

(since the  recursion levels can be absorbed into the Big-O-Tilde notation).

recursion levels can be absorbed into the Big-O-Tilde notation).

If we unwrap the running time into standard Big-O notation, we get

Is it practical? At first glance, the triple-logarithmic factor might seem like a deal breaker for this algorithm. It turns out the actual performance is pretty reasonable. This paper found that the algorithm takes time roughly 7.65 seconds per thousand keys, meaning it would take a little more than 13 hours to run on 6.2 million keys.

One of the log factors can be removed using a slightly more clever variant of the algorithm, which avoids GCD computations at all but the first level of recursion (See this paper). The improved algorithm takes about 4.5 seconds per thousand keys, resulting in a total running time of about 7.5 hours to handle 6.2 million keys.

So there we go. A computation that should have taken years is reduced to a matter of hours. And all it took was a bit of clever recursion.

RSA encryption allows for anyone to send me messages that only I can decode. To set this up, I select two large random primes

The beauty of RSA encryption is that using only the information I publicly released, anyone can encode a message they want to send me. But without knowing the values of

On the surface, RSA encryption seems uncrackable. And it might be too, except for one small problem. Almost everyone uses the same random-prime-number generators.

A few years ago, this gave researchers an idea. Suppose Bob and Alice both post public keys online. But since they both used the same program to generate random prime numbers, there’s a higher-than-random chance that their public keys share a prime factor. Factoring Bob’s or Alice’s public keys individually would be nearly impossible. But finding any common factors between them is much easier. In fact, the time needed to compute the largest common divisor between two numbers is close to proportional to the number of digits in the two numbers. Once I identify the common prime factor between Bob’s and Alice’s keys, I can factor it out to obtain the prime factorization of both keys. In turn, I can decode any messages sent to either Bob or Alice.

Armed with this idea, the researchers scanned the web and collected 6.2 million actual public keys. They then computed the largest common divisor between pairs of keys, cracking a key whenever it shared a prime factor with any other key. All in all, they were able to break 12,934 keys. In other words, if used carelessly, RSA encryption provides less than

At first glance this seems like the whole story. Reading through their paper more closely, however, reveals something strange. According to the authors, they were able to run the entire computation in a matter of hours on a single core. But a back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that it should take years to compute GCD’s between 36 trillion pairs of keys, not hours.

So how did they do it? The authors hint in a footnote that at the heart of their computation is an asymptotically fast algorithm, allowing them to bring the running time of the computation down to nearly linear; but the actual description of the algorithm is kept a secret from the reader, perhaps to guard against malicious use. Within just months of the paper’s publication, though, follow-up papers had already discussed various approaches in detail, both presenting fast algorithms (see this paper and this paper), and even showing how to use GPUs to make the brute-force approach viable (see this paper).

There’s probably a lesson here about not bragging about things if you want them to stay secret. But for this post I’m not interested in lessons. I’m interested in algorithms. And this one turns out to be both relatively simple and quite fun.

Algorithm Prerequisites: Our algorithm will deal with integers having an asymptotically large number of digits. Consequently, we cannot treat addition and multiplication as constant-time operations.

For

Computing the GCD naively using the Euclidean algorithm would take

Fortunately, all of these algorithms are already implemented for us in GMP, the C++ big-integer library. For the rest of the post we will use Big-O-Tilde notation, a variant of Big-O notation that ignores logarithmic factors. For example, while GCD-computation takes time

Transforming the Problem: Denote the set of public RSA keys by

The Algorithm: The algorithm has a slightly unusual recursive structure in that the recursion occurs in the middle of the algorithm rather than at the end.

At the beginning of the algorithm, all we have is the keys,

The first step of the algorithm is to pair off the keys and compute their products,

Next we recurse on the sequence of numbers

Our goal is to compute

and that when

To see why this is the case, one can verify that the term on the right side of the GCD is guaranteed to be a multiple of

Computing each of the

Bounding the Running Time: Let

Therefore each of the

If we unwrap the running time into standard Big-O notation, we get

Is it practical? At first glance, the triple-logarithmic factor might seem like a deal breaker for this algorithm. It turns out the actual performance is pretty reasonable. This paper found that the algorithm takes time roughly 7.65 seconds per thousand keys, meaning it would take a little more than 13 hours to run on 6.2 million keys.

One of the log factors can be removed using a slightly more clever variant of the algorithm, which avoids GCD computations at all but the first level of recursion (See this paper). The improved algorithm takes about 4.5 seconds per thousand keys, resulting in a total running time of about 7.5 hours to handle 6.2 million keys.

So there we go. A computation that should have taken years is reduced to a matter of hours. And all it took was a bit of clever recursion.

Comments

Post a Comment