Last September, seven months after Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Yale historian Timothy Snyder took a 16-hour train ride from Poland to Kyiv. Snyder knew the city well: he’d been visiting since the early 1990s, when he was a graduate student and the newly post-Soviet Ukrainian capital was dark and provincial. In the decades that followed, Kyiv had grown bigger and more interesting, and Snyder, who is now 53, had become an eminent historian of eastern Europe. On disembarking at the Kyiv-Pasazhyrskyi station, he found the city transformed by war. There were sandbags everywhere, concrete roadblocks and steel “hedgehogs” designed to stop Russian tanks. Air raid warnings blared from phones in pockets and handbags.

Not everything was unfamiliar. The first months of the war had gone relatively well for the Ukrainians – a fact that surprised many observers, but not Snyder – and by September, Kyiv was no longer in imminent danger of occupation. Life, while not normal, was regaining some of its prewar rhythms. You could get a haircut at a barbershop, or hear standup at a comedy club, or sunbathe on the shores of the Dnieper River.

Snyder had come to speak at an annual conference, Yalta European Strategy (YES), which was founded in 2004 to promote ties with Europe. Funded by a Ukrainian oligarch, the conference had become an occasional stopover for the gladhanding global elite. Bill and Hillary Clinton, Gordon Brown, Elton John and Richard Branson had all participated in previous years, and the roster for the 2022 meeting included the American national security adviser, Jake Sullivan, and Eric Schmidt, the former CEO of Google.

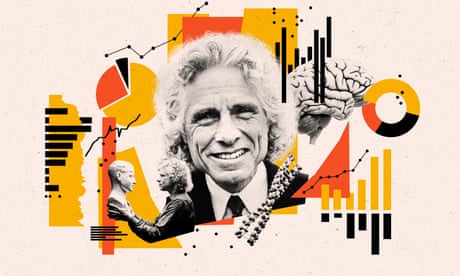

Though he is not a natural gladhander, Snyder had attended the conference before. His first visit came in 2014, a few years after he published Bloodlands, a provocative and emotionally devastating account of Nazi and Soviet atrocities, which established him, in the words of one reviewer, as “perhaps the most talented younger historian of modern Europe working today”. The book was a crossover success, and in the years that followed Snyder began to write more about contemporary issues, including the climate crisis, healthcare and Ukrainian politics. But it was his writing about two figures, Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin, that turned him into one of the most prominent American intellectuals of the past decade.

Snyder’s mainstream breakthrough, in 2017, was On Tyranny, a bestselling little book that helped make him the house intellectual of the centre-left anti-Trump movement sometimes known as #resistance liberalism. The book earned him regular invitations to appear on television. (“Whether or not you talked to your friends about it, everybody you know has been reading and re-reading On Tyranny,” Rachel Maddow said on her show.) The news Snyder brought his audience was almost unremittingly bleak, yet it also offered a strange kind of reassurance. You are not wrong to feel that the situation is grievous, Snyder told them. Take it from an expert in political barbarism: things are exactly as bad as they seem.

Snyder’s dire warnings were easy to caricature as bourgeois-liberal doomerism, yet Trump’s attempts to overturn the 2020 election allowed him to claim vindication for what his critics had seen as hyperbole. On 9 January 2021, three days after a mob laid siege to the US Capitol, Snyder published an essay in the New York Times that made another prescient prediction. Trump’s failed putsch was more like the beginning than the end of something, Snyder argued. Since Trump’s “big lie” – that he won the election – “was now a sacred cause for which people had sacrificed”, it would remain a potent force in American politics unless a concerted effort was made to stop it.

Snyder’s view of Putin was still more ominous. In Putin’s Russia, Snyder sees a corrupt autocracy that has turned to neo-fascism in an attempt to regain its imperial glory. He was one of the few anglophone commentators to anticipate Russia’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine – a prediction that even his friends scoffed at – and warned in his book Black Earth that “a new Russian colonialism” threatened European stability. In his opinion, the full-scale invasion that started last year was not, as some saw it, a minor regional conflict, but rather an atrocity of epochal significance: “It is about the possibility of a democratic future,” he wrote in Foreign Affairs.

Over the past year, Snyder has been one of the most eloquent interpreters of the war in Ukraine. He writes and speaks frequently about the conflict – including, in mid-March, to the UN security council. He has established a project to document the war, and more controversially, has raised more than $1.2m for an anti-drone defence system. A course on Ukrainian history that he taught at Yale last autumn has had hundreds of thousands of views on YouTube, and he has become one of the most famous western intellectuals within Ukraine itself. “He used to be a celebrity in historical circles and among intellectuals,” his friend, the Ukrainian rock star Sviatoslav Vakarchuk, told me recently, “but now even ordinary people know a lot about him.”

It was a sign of Snyder’s standing that the YES conference was only the second-highest-profile stop on his Kyiv itinerary. The main reason for his trip, Snyder told me, during one of three long conversations we had recently, was a private meeting with Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelenskiy. The Ukrainians, Snyder said, “think I’m much more important than I actually am”. Zelenskiy, he went on, “thought of me mainly as somebody who had some kind of voice. I’m not under the illusion that … ” Snyder stopped himself. “Well, no, that’s not true. He said: ‘My wife and I have read On Tyranny.’ That’s the first thing he said when I met him.”

Sitting in green leather wingbacks in Zelenskiy’s presidential office, the men talked for more than two hours. They discussed Shakespeare, the Czech playwright and politician Václav Havel, and the Soviet physicist and dissident Andrei Sakharov. They talked about freedom, too, the subject of a new book Snyder is working on, and particularly about Zelenskiy’s decision to stay in Ukraine once the invasion began. Zelenskiy said that while most western observers had expected him to flee, he had never felt as if he had any real choice. “That’s an argument that he helped me to make,” Snyder told me. “Being free means that you actually end up in situations where you won’t actually feel like you have a whole bunch of options.”

Snyder’s fascination with what he has described as Zelenskiy’s “choiceless choice” is not surprising: he had predicted that, too, on the eve of the war. As an academic and a public intellectual, Snyder has long operated on the belief that “there are moments in the world where your actions are magnified. It may be that you can take things that were going to swerve in a particularly bad direction, and you can push them with relatively little effort.” Zelenskiy’s decision, like the Ukrainian resistance writ large, was for him a vivid demonstration that this belief was well justified.

Unusually for a serious historian, Snyder often draws analogies between the past and the present. More unusually still, he routinely makes predictions about the future. What he calls his “Cassandra mode” is different from his historical work, but not entirely disconnected. “History isn’t the boring recitation of stuff that we all know but have forgotten,” he says. “It’s a constant, exciting discovery of things that actually happened, which weren’t anticipated and which were probably considered wildly improbable at the time. The first world war, the Holocaust: a lot of the things which seem absolutely foundational were regarded at the time as ridiculous, absurd, impossible. And once you know that, then you can have the intuition that, well, maybe in this moment right now there’s something happening which people aren’t seeing.”

Snyder was raised in a Quaker family in south-western Ohio, and he retains a midwestern faith in the virtue of saying plainly what you mean. His unadorned prose has the sturdy simplicity that one associates with Shaker furniture. Unlike most academics, he also feels a deep responsibility to explain his ideas as straightforwardly as possible. “It’s very, very easy to hide behind the notion that, ‘Oh, what I do as a philosopher or psychologist or cell biologist is just really complicated,’” he says. “I honestly don’t believe that’s true.”

Snyder dislikes the scholarly tendency to hide judgments under a cloak of pseudo-objectivity. He has a strong moral feeling – his wife, Marci Shore, calls it a “save-the-world impulse” – that can be traced back to his parents. Shore told me that Snyder’s mother “has this very calming sense of moral clarity. It’s like, there are no perfect decisions in the world. There’s no space of innocence. Given the situation as it is, you make the choice and you go forward.” Snyder, she says, is much the same way.

Shore, who is also a historian at Yale, noted her husband’s deep confidence in his abilities. Over email, she told me a story about the birth-preparation class she and Snyder had taken when she was pregnant with their son. They were living in Vienna, and the midwife spoke to the class in Wienerisch, the colloquial Viennese dialect. After the class, the couple agreed they had understood only about 60% of what they’d heard. “The difference between us can be gleaned in this small but revealing detail,” Shore wrote. “Tim was calmly persuaded that the 60% we did understand was the important part, whereas I was convinced that the 40% we didn’t understand was surely what was crucial.”

As Snyder’s public profile has risen, he has attracted an increasing number of critics. His judgments have been controversial in part because his own politics are difficult to pin down. To Ukrainian nationalists, he sounds like an American leftist. To American leftists, he sounds like a Ukrainian nationalist. His books carry blurbs from an unlikely coterie that ranges from George Saunders, author of Lincoln in the Bardo, to Henry Kissinger, author of the bombing of Cambodia. In Snyder’s focus on the evils of nazism and Stalinism and his advocacy of US military support for Ukraine, some people see the makings of a barely reconstructed cold warrior, yet he opposed the Iraq war and is anything but blithe about the US’s claims to moral supremacy. His memoir-diatribe Our Malady lambasted the US’s privatised healthcare system, and lately he has been speaking out against Republican-sponsored laws that limit discussion of the US’s racist history in schools.

Perhaps the most common critique of Snyder over the past decade has to do with the stridency of his public arguments, which often see him presenting beliefs, and even speculations, as incontrovertible facts. Earlier this year, after an FBI counterintelligence official was indicted for violating sanctions against a Russian oligarch, Snyder wrote on his Substack: “We are on the edge of a spy scandal with major implications for how we understand the Trump administration, our national security, and ourselves.” Two weeks later, he ridiculed discussions about a potential nuclear escalation in the Ukraine conflict as “wrong, and embarrassingly so” in moral and strategic terms. “That is the most important thing to say about nuclear war: it’s not happening,” he claimed.

This rhetorical self-assurance is a crucial feature of his mainstream appeal: for audiences disoriented by some of the most politically turbulent times they’ve ever seen, Snyder’s authoritative tone suggests a firm hand on the tiller. Yet it also supplies grist for critics who think Snyder is too ready to see catastrophe lurking around every corner. The cultural critic Lee Siegel accused him of being “a one-man industry of panic, a prophet whose profitability depends on his prophecies never coming true”. The political scientist Daniel Drezner, in the New York Times, described On Tyranny as “overwrought” and potentially “self-defeating because of its hyperbole”. And in the Nation, Sophie Pinkham described The Road to Unfreedom, Snyder’s 2018 book about Putin and Trump, as “the apotheosis of a certain paranoid style that has emerged among liberals in Trump’s wake”.

Shore told me that her husband possesses “a kind of strange composure” that allows him to absorb criticism without emotional disturbance. Snyder, for his own part, told me that he doesn’t see much value in addressing his critics directly. He nevertheless makes no apologies for stating clearly what he thinks will happen. And while Snyder is proud of his foresight – he has often been correct – he also insists that his predictions are not a parlour game to rack up points. Central to his understanding of history is a conviction that events are not predetermined by broad structural forces such as economics or technology. His dire analogies and doomy premonitions are not meant to make people depressed or complacent. Quite the opposite. To make predictions is to emphasise the unpredictability of the future, to remind readers that they might still have the freedom to change history.

In February, I went to New Haven to watch Snyder teach at Yale. His morning class, on a cold and sunny Valentine’s Day, was an undergraduate seminar on mass incarceration in the US and USSR. He was teaching the course with the philosopher Jason Stanley, a close friend of his who had likewise become a pillar of the anti-Trump #resistance. The course was held in a classroom with dark wood wainscoting, a black marble fireplace, and gothic-arch windows inset with scenes from the Bible. Through the window it was possible to see the 14-storey tower that had been renamed in honour of the university’s recently deceased chief investment officer.

Though Snyder can sometimes seem, in print, like an author unfamiliar with the concept of self-doubt, in person there is still a trace of the “lanky, somewhat diffident undergraduate” that one of his professors recalls from his university days. He has a dry humour and a talent for extemporaneous eloquence, but no one would mistake him for a commanding presence. He speaks softly and dresses in textured grays and browns that might as well be camouflage on a north-eastern American college campus in winter. Amplifying this self-effacing air is a sense, which hangs about him like a penitential sackcloth, that there is too much to do, too many legitimate requests on his time. “I can’t physically process the email,” he told me at one point. “I’m just a history professor. I don’t have staff.”

When he arrived in the seminar room, Snyder provoked no murmur or hush among the students. With his thinning white hair, his lively blue eyes, and his air of relaxed reticence, he made for a distinct contrast with Stanley, who showed up to the course in black clothes and black sunglasses, and quickly started cracking loud jokes with the students nearest his chair.

The subject for the day’s class was late-19th-century scientific racism, but Snyder said that he wanted to start with a reminder about some philosophical arguments connected to the subject at hand. Without notes, he launched into a brief lecture that touched on Plato’s Parmenides, the Book of Genesis, the idea of dialectic in Hegel and Marx, and the treatment of history by the French-American polymath René Girard, before wrapping around to WEB Du Bois. Shore had told me that socialising and speaking in public can be draining for Snyder, but it was clear in the seminar room that he was enjoying himself. He spoke quickly and fluently, gesturing with his hands and unspooling his arguments in transcription-ready sentences.

A few hours after the class ended, Stanley explained the detour to Plato. Earlier that morning, he told me, Snyder had texted to say that he wanted to remind the students of some earlier thinkers. “I said, ‘What are you talking about, Parmenides?’ as a joke,” Stanley recalled. “He took it as a dare. That’s very standard. Tim is extremely competitive.”

Snyder’s friends sometimes marvel that the eldest son of a veterinarian from Ohio with no familial ties to eastern Europe became a leading expert on the region. His family can trace its ancestry back many generations on each side in the US, and he grew up not far from the farms where his grandparents grew pumpkins, soya beans and corn. His parents were Quakers who served in the Peace Corps in the Dominican Republic and El Salvador before returning to Centerville, a prosperous suburb outside Dayton, to raise their family.

Snyder says that his parents were “very leftwing, and not just by American standards”, an inclination that set them apart from the conservatism that prevailed in the suburbs and countryside of south-western Ohio. In the midst of an overwhelmingly Republican milieu, they hung posters celebrating leftwing Latin American causes on their walls and regularly sat down with their three boys to write letters to prisoners for Amnesty International on Sunday afternoons. When Snyder was in the ninth grade, the family traveled to a Quaker dairy commune in Costa Rica. “That was our idea of tourism,” he said.

An alienated and mostly indifferent student in high school, Snyder bucked against his parents’ leftist politics by flirting with libertarianism. He remembers debating the virtues and vices of the Soviet Union with his mother. “Her starting point would be, ‘Well, they were on the right side with Nicaragua. They were on the right side with Cuba.’ It wouldn’t be Hungary in 1956 or Czechoslovakia in 1968.” Still, there were limits to his rebellion. “I would have never thought, ‘I’m for Reagan.’ Even at my most midwestern buttoned-up, that would have been a different tribe.”

When Snyder arrived at Brown University in 1987 as an undergraduate, he thought he might end up as a lawyer working on nuclear arms control. Two classes would get him interested in history. One was a survey of European intellectual history taught by Mary Gluck. The other, on postwar eastern European history, was taught by Thomas W Simons Jr, who would soon after be appointed ambassador to Poland. That course started less than two weeks after Nicolae Ceaușescu, the Romanian dictator, was executed in Bucharest on Christmas Day 1989. “I thought I’d get 15 or 20 students,” Simons told me. “A hundred and thirty showed up.” Snyder says he was “obsessed” with the course, so much so that he suggested Simons turn his lecture notes into a book. Simons hired him the following summer to help him do just that.

After graduating, Snyder attended Oxford on a Marshall Scholarship. Timothy Garton Ash, one of his DPhil advisers, recalled Snyder as “a very reserved young man” who nevertheless stood out from his peers for his moral intensity, analytical clarity and intellectual boldness – which saw him “pushing an argument as far as it would go, or possibly even a little farther”.

In his dissertation, on the Polish Marxist thinker Kazimierz Kelles-Krauz, and especially in his second book, The Reconstruction of Nations, which he’d largely completed by the time he got hired at Yale in 2001, it is already possible to see Snyder engaging with the major themes that would shape his subsequent work. The first was that eastern Europe was not an ahistorical no-man’s land trapped between Europe and the Soviet Union, but a place with its own agency and its own history. The second was that history could be shaped by individual human choices. The third was the importance of ideas as a primary mover of historical events, particularly the fraught idea of the nation.

Since college, Snyder had nurtured what he describes as “larger ambition to be – it sounds very pompous, but to be an intellectual, a writer”. Bloodlands, published in 2010, marked the first major inflection point in his public career. By that time, he had already been writing occasionally for non-academic audiences. But his powerful account of the human toll of Nazi and Soviet horror won him his first major audience among non-academic readers.

Snyder took as his subject the “political mass murder” of 14 million people that occurred between 1933 and 1945 in a swath of eastern Europe that stretched “from central Poland to western Russia, through Ukraine, Belarus and the Baltic states”. From this simple formula, Snyder drew several arguments. He suggested, for instance, that the Nazis and the Soviets treated the countries of the “bloodlands” – the term alludes to an Anna Akhmatova poem – as proximate colonies. He also argued that too much of the previous research on the killings had seen them through the eyes of the major powers. More fundamentally, his book proposed that the events that transpired in these countries ought to be seen as central to 20th-century European history.

Among academics, Bloodlands won praise for Snyder’s wide learning: he speaks five languages, reads five more, and belonged to the first generation of western scholars to gain widespread access to eastern European archives after the fall of communism. There was also criticism. Some reviewers balked at his juxtaposition of the Holocaust with Stalin’s crimes, while others – notably Richard J Evans, in a particularly vehement article – accused him of failing to explain the causes of the events he was describing. (In Black Earth, his far more controversial follow-up to Bloodlands, Snyder seemed to have both criticisms in mind: its subject was the causes of the Holocaust.) Yet Snyder’s provocative efforts to reframe European history brought new energy to what was already coming to be seen as settled history. “That whole history had been told as a story of Russia and Germany, and of course, the Holocaust,” Garton Ash told me. Bloodlands, he said, “put the spotlight on east-central Europe in a way which changed the historical perspective.”

Snyder believes that doing good history requires taking bad ideas seriously, and he applies the same principle to his writing on current events. “Bad ideas matter,” he says. “They have their own coherence and their own power.” Shortly after he published Bloodlands, he noticed that Putin, who was serving a term as prime minister, was speaking with concerning frequency about the essential unity of Russia and Ukraine. In 2013, Putin visited Kyiv for the 1,025th anniversary of the baptism of Prince Vladimir the Great. In Kyiv, Snyder says, Putin “gave this wacky speech saying that Ukraine and Russia were one because of the baptism, and no one could do anything about it because it was beyond politics. It was a spiritual truth: basically God made it so.”

The Maidan uprising began that November in Ukraine. It was sparked by the sudden refusal of Ukraine’s president, Viktor Yanukovych, under pressure from Russia, to sign an association agreement with the European Union. The protests grew to more than half a million people, and by January the protesters were locked in an increasingly deadly standoff with the state. On 3 February 2014, Snyder published an op-ed in the New York Times under the headline “Don’t Let Putin Grab Ukraine”. Citing Putin’s increasingly vocal desire for a Eurasian Union to rival the EU, as well as Russian officials who had been openly discussing the partition of Ukraine, he warned that Putin might try to engineer a coup in Kyiv. If that failed, he suggested, Putin might see “armed intervention” as the only way to save face.

Snyder says his warning was a “judgment call” based on his sense that Putin was driving the Ukraine policy more than people realised. “When I read those angry things that he published in Russian newspapers about civilisation, his anger didn’t seem to be tactical. It seemed to somehow come from someplace deep.” The other factor that triggered Snyder’s suspicion was “a very visible uptick in anti-Ukrainian propaganda, along the lines of, ‘They’re Nazis. They’re gay. They’re gay Nazis.’ On Russian television, in November and December of 2013, it became very carnivalesque, and that got me thinking that something was in the works.”

Snyder’s concern about Russian aggression was not widely shared. Western news reports from the time repeatedly assured their readers that Putin would not be so rash. (“Most experts […] dismiss the possibility of military force,” the Times said, a week after it ran Snyder’s op-ed.) Serhii Plokhii, a Ukrainian historian at Harvard who is friendly with Snyder, told me that he’d been certain the op-ed went too far. Yet just a few weeks later, after Yanukovych fled the country, Russia seized Crimea and sent troops into eastern Ukraine. Plokhii, laughing at the memory, said he spoke to Snyder not long afterward. “I told Tim: ‘OK, I thought you were a complete nut.’”

Snyder says that at the time of the invasion, there had been a tendency to treat Russia as though it were merely a failed or corrupted version of a western liberal democracy. “Both the American and the German view of Putin was about denied agency. They’re like, ‘Oh, well, they’re trying to have a transition, but it’s hard for them, poor souls, therefore they have to invade Georgia or Ukraine.’” By contrast, he said, “if you say Putin is a guy who reads, and changes, and pulls in ideas, you’re saying, ‘OK, he’s not an idiot. He’s not predictable. He makes moves we wouldn’t expect.’” This is one of the reasons Snyder insists on calling Putin fascist: “It sounds weird, but to say that he is influenced by fascism is to give him credit. He’s not just a historically determined piece in this story of transitions. He’s been doing something different for more than a decade.”

Two years after the annexation of Crimea, Snyder noticed that Russian politicians and state media outlets were spreading the same kinds of propaganda and misinformation about the US that it had about Ukraine. Though it is not true, as Snyder claimed recently on Twitter, that he “broke the story of Trump and Putin,” he was early in devoting sustained attention to the incipient relationship between the two men. In April 2016, he argued that Trump’s weakness and vanity made him an easy mark for Putin, who had already started cultivating him “as a future Russian client”.

By that autumn, it was becoming clear that Russia was behind the hack-and-leak campaign that generated weeks of unfriendly headlines for Hillary Clinton in the final stretch of the presidential campaign. Citing Putin’s rehabilitation of Ivan Ilyin, a 20th-century Christian fascist philosopher, Snyder argued that there was a logic, and even a political philosophy, behind the apparent chaos of the cyber-attacks. “If democratic procedures start to seem shambolic,” he wrote in the New York Times, “then democratic ideas will seem questionable as well. And so the US would become more like Russia, which is the general idea. If Mr Trump wins, Russia wins. But if Mr Trump loses and people doubt the outcome, Russia also wins.”

A few days before the election, Snyder flew back to his native Ohio to canvass for Clinton. “They assigned me literally the neighbourhood where I grew up,” he recalled. “I was struck by how people didn’t want to have a conversation. I mean, I’m an introvert, but I was a harmless-looking white guy, and I had a lot of trouble getting people out to talk.” When he got home, he told Shore that Trump was going to win Ohio. Still, he thought Clinton would prevail overall. “I think there was a certain amount of white naivete,” he says.

“Tim always kind of believed in America more than I did,” Shore says. “He’s not used to being wrong, like really wrong. And he really didn’t think Trump was going to win. When I told the kids the next morning, my daughter, who was four at the time, said, ‘Maybe Daddy forgot to tell someone to vote for Hillary Clinton.’”

Snyder was stunned by Trump’s victory, but it also provided the immediate impetus for On Tyranny. Flying home from Sweden after the election, he started writing a list of lessons for thwarting tyranny on an aeroplane napkin. The list included advice such as “Do not obey in advance” and “Defend institutions”. He posted it on Facebook when he got home, and the post went viral. Snyder’s editor told him they could publish it as a short book if he added some context to each lesson. The result – which saw Snyder’s plain declarative sentences become plain imperative exhortations that drew from the history of European political terror – more closely resembles a samizdat manifesto than one of his heavy historical volumes. Thanks to its urgency and its brevity, the book became a totem for Americans horrified by their new president. On Tyranny sold more than half a million copies during Trump’s term of office, and spent nearly two years in total on the New York Times bestseller list.

The exaltation of Snyder among centre-left liberals prompted an equal and opposite reaction within certain quarters of the American left. For these critics, Snyder’s portentous analogies and breathless warnings smacked of historical naivete and ideological convenience. To imply that Trump was a Hitler in waiting was not only to overlook the native horrors that American politics had conjured in the past – it was also to neglect the ways that a bipartisan programme of neoliberalism had created the conditions that led to Trump’s election. Writing in August 2017, Samuel Moyn and David Priestland, historians at Yale and Oxford, criticised the views that “democracy is under siege” and “totalitarianism is making a comeback” as forms of hysterical and counterproductive “tyrannophobia”, a barely veiled shot at Snyder. “The sky is not falling and no lights are flashing red,” they wrote.

It is not hard to guess why On Tyranny became a target for leftists annoyed with efforts to draft them into an anti-Trump popular front. The 2016 election witnessed the first serious resurgence of socialism in the US in half a century, and many on the left were not in a mood to make nice with the mainstream liberals who had failed to stop Trump at the polls. Yet Snyder was never a neoliberal triumphalist. Nor was he complacent about the US’s failures. “I honestly think this is just something people want to be true, because it would be comfortable if true,” he told me. In previous writings, he had denounced free-market fundamentalism, and in the epilogue of On Tyranny itself, Snyder wrote that the danger of Trump was that he would usher the US from “a naive and flawed sort of democratic republic to a confused and cynical sort of fascist oligarchy”. What Snyder hoped for was something different from either option – “a renewal”, as he would put it in his next book, The Road to Unfreedom – “that no one can foresee”.

Snyder admits that when he wrote On Tyranny, he did not sufficiently account for the ways in which Trump was a familiar type in American history: “My take was that this was new and dangerous. I was probably a little bit wrong about the new part.” But he says he was correct about the extent to which people would tell themselves, “America’s exceptional and nothing bad can happen here.” Throughout Trump’s presidency, he continued to warn that Trump would try to hold on to power unlawfully, and in the essay he published a few days after the siege of the US Capitol, he didn’t pass up the chance for a moment of self-congratulation. “It was clear to me in October that Trump’s behavior presaged a coup,” he wrote, “and I said so in print.”

Even Moyn, who calls his colleague “an extraordinarily gifted human being,” doesn’t dispute Snyder’s right to claim prescience. In their 2017 op-ed, he and Priestland had asserted that “there is no real evidence that Mr Trump wants to seize power unconstitutionally, and there is no reason to think he could succeed”. Moyn told me he still holds that view today, even after the 6 January siege. “I don’t believe that democracy was ever on the brink,” he said. Yet he also acknowledged that “It almost doesn’t matter for me to say I don’t think it provided that vindication, because everyone else thought it did”. In the popular mind, he conceded, Snyder “won the debate about Trump”.

Right up until the attack came, Snyder was still unsure whether to expect another Russian invasion of Ukraine. “There wasn’t a propaganda rollout the way there had been in 2014,” he says. “My normal intuitions come out of Russian propaganda, and they were starving me.” In late February, he was in New Haven, teaching two courses at Yale plus a third, on freedom, at a prison in central Connecticut. After the war began, on 24 February, he and Shore cancelled the family holiday they’d been planning. “It didn’t feel morally right,” he said.

Jason Stanley told me that the war was “not abstract” to Snyder: “One always has to remember that. These are his friends. Tim takes friendship extremely seriously. These are people he’s known for decades.” Yet it is also true that the war represents a stark illustration of the themes that have shaped Snyder’s work over the past three decades. Most obviously, Ukraine’s surprisingly successful defence efforts offer an instance of the sort of geopolitical agency that he has, in his work, tried to restore to the historiography of eastern Europe. Putin’s war has also provoked crucial questions about Ukrainian nationhood and the Ukrainian state, of precisely the kind that Snyder has spent his career investigating. And while Snyder predicted that the outcome will be decided by material factors – humanitarian support, debt forgiveness, weapon deliveries – he also sees the war as a fight about ideas. To Snyder, Putin’s repeated claims about the spiritual unity of Russian and Ukrainian nations are not mere propaganda meant to obscure a hard-nosed strategic calculation. They are part of a deeply held neo-imperial vision that Putin has cobbled together from his reading of Ilyin, from Soviet history, and from a more general sense of Russian greatness.

This emphasis on ideas has led Snyder to be criticised by some in the realist school of international relations. Emma Ashford, a senior fellow at the Stimson Center, a thinktank, counts herself an admirer of Snyder’s historical work, but she also says that his “understanding of world affairs is almost indelibly shaped by what he thinks are the big important ideas, whereas I would say that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was motivated as much by trying to prop up its falling security in the region”. The dispute is not academic. If you believe, as Ashford does, that Russia is motivated by strategic fears, then every additional degree of western involvement risks exacerbating the original causes of the war and prolonging the conflict. By contrast, if you believe with Snyder that the war’s roots lie in Putin’s fascist worldview, then victory on the battlefield becomes imperative. “A lot of smart people have said it before me, but fascism was never discredited. It was only defeated,” he says. “The Russians have to be defeated, just like the Germans were defeated.”

In 2004, as protests against corruption and electoral fraud were building into what would become the Orange Revolution, Snyder wrote that “Ukraine today is the test for Europe”. Nearly two decades later, it seems clear that he sees the war in Ukraine as a test not only of Europe and the US, but of himself. After he returned from Kyiv last autumn, he was asked to become an “ambassador” for United24, a crowdfunding effort that Zelenskiy had launched in the early days of the war. The campaign’s organisers suggested that he might want to raise funds for the reconstruction of a library in Chernihiv, which had been destroyed by Russian shelling early on in the war.

“I thought about that,” Snyder says. “I knew the library. I knew Chernihiv. I was there in September, and I’d seen the ruins. It would have been a perfectly natural thing for me, as a historian, to do. No one’s going to say, ‘Oh, you’re doing something wrong by raising money for the library.’” But Snyder didn’t want to decide based on what felt “politically correct” or easiest for him personally. Instead, he asked his Ukrainian friends what would be most useful. “They all said, ‘Drones’. The historians said, ‘Drones’. The humanists said, ‘Drones’. The peace activists said, ‘Drones’.”

I asked Snyder whether he’d have done the same had his friends in Kyiv said that an offensive weapon was needed – a battle tank, say? “No,” Snyder said. “You got me there.” The anti-drone system was a weapon, he acknowledged. “But it’s a weapon meant to save civilian lives at a time when Russia was openly threatening to take out the infrastructure, and to try to starve and freeze out as many people as they could. You can’t stop that by rebuilding a library. You can’t stop a drone by political correctness. But if they had said, ‘Would you help us fund a tank?’ I would have said no. I think that probably just shows the limit of my willingness to take hits. It would probably be OK to raise money for a tank.”

Even with the drone catcher, Snyder says, “I knew, 100%, that people were going to say, ‘Look at him. He’s an activist. He’s raising money for a government.’” He was thinking particularly of his critics in Germany, “whose version of being a public intellectual is criticising other people for being public intellectuals”. Snyder raised more than $1.2m for the anti-drone system in under three months. The criticism came as expected, and he says it only confirmed to him that he had made the right choice.

In Thinking the Twentieth Century, a book that Snyder helped the historian Tony Judt compose before he died in 2010, Judt argued that contemporary public intellectuals faced a choice between writing thoughtfully for a small audience or becoming what he called “a media intellectual”: “This means targeting your interests and remarks to the steadily shrinking attention span of TV debates, blogs, tweets, and the like.” These were alternatives, not complements, Judt insisted. “It is not at all obvious to me that you can do both without sacrificing the quality of your contribution.”

Not everyone would agree that Snyder has fully escaped the horns of Judt’s dilemma, but so far he has managed enough of what he calls “professional hygiene” to avoid too much cross-contamination. The Ukraine course he taught at Yale and on YouTube might fairly be described as pro-Ukrainian, in the sense that it offered a thoroughgoing rebuttal of Putin’s assertion that “Ukraine is not a real country”. But the millennium-long story it told was complex and surprising, nothing at all like the pithy, almost propagandistic appeals Snyder was writing on Substack.

Snyder says he feels no philosophical tension between his work as a historian and his advocacy. He also tends to downplay any concern about any potential effects of the war on his own reputation. Still, in tying himself so completely to the Ukrainian self-defence effort, he has put himself on the line in a way that is rare for a public intellectual of his stature. Wars are messy, after all, even wars that offer what he calls “an unusual amount of moral clarity”. And the questions that Ukraine will soon need to confront – how to end the war, how to rebuild the country in its aftermath – will probably need answers that cannot be provided by uncomplicated appeals to basic values.

Sviatoslav Vakarchuk, the Ukrainian musician, said of his friend, “Some people think he’s a romantic. I would say, he’s not a romantic, he’s an idealist.” The distinction seems apt. Snyder is not Christopher Hitchens: he doesn’t long for the existential thrill of whistling artillery and crossfire overhead. “I certainly don’t feel like the Ukraine war is a fulfilment of my destiny, or anything like that,” he told me. Yet his faith in the power of ideas has an important corollary: an idea that costs you nothing is worth exactly what you paid for it. As he put it, during our last conversation in New Haven, good ideas “aren’t real unless you’re willing to do some little thing to act on them”.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/mar/30/how-timothy-snyder-became-the-leading-interpreter-of-our-dark-times-putin-trump-ukraine

Comments

Post a Comment